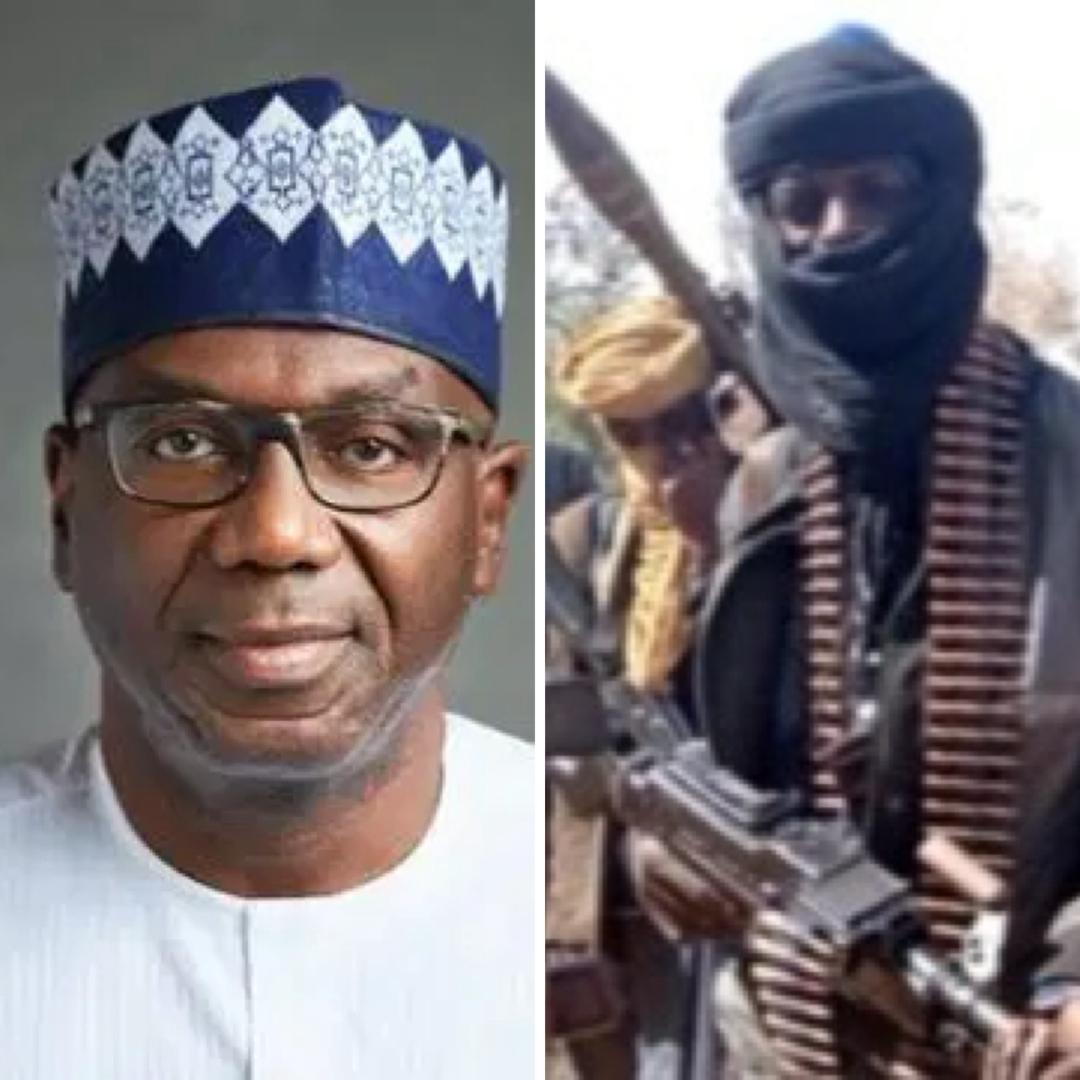

From “Fit for a Child” to a State of Emergency: How Abdulrahman Abdulrazaq Failed Kwara’s Children

Sulaiman Onimago

In 2010 under a visionary Leader, Former Governor AbubakarBukolaSaraki, Kwara State earned a rare recognition from UNICEF. It was declared “fit for a child”, not because of sentiment, but because it had earned the label. The state had domesticated the Child Rights Act ahead of most others in Nigeria. It wasn’t just a legal checkbox; Kwara matched its signature with serious intent. It established family courts, strengthened protection institutions, and invested in the kind of social infrastructure that made international partners nod in agreement rather than sigh in frustration.

It was during the Bukola Saraki administration, a time when governance was structured, measured, and focused on people, not applause. So effective were those years that UNICEF had no need to run direct intervention programmes in Kwara. That’s not a snub; that’s a sign of trust. UNICEF did not ignore Kwara; they simply had no emergency to respond to. The system was working.

Fifteen years later, and that headline has mutated into a humanitarian tragedy. In 2025, UNICEF is back, not with medals, but with emergency supplies. According to recent reports, over 300,000 children in Kwara are severely malnourished, prompting UNICEF to deploy RUTF (Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food) usually reserved for disaster zones, refugee camps, and famine-stricken regions. That a once-praised state now sits in the same nutritional emergency column as war-torn areas is not just an embarrassment; it is a scandal.

Let’s not pretend, this is complicated. Malnutrition on this scale doesn’t just fall from the sky. It is not a natural disaster; it is a man-made crisis, constructed by neglect, sealed by silence, and delivered through poor leadership. Since 2019, Kwara has witnessed a steady erosion of public accountability, policy depth, and developmental vision. It’s as though the state was handed to a leadership allergic to follow-through and more interested in optics than outcomes.

And yet, the present administration continues to parade a few well-fed, well-dressed success stories, as though the rare exception justifies the abandonment of the multitude. We are served images of the governor hugging high-performing students while hundreds of thousands of others are physically shrinking from hunger. It’s a curious form of governance: highlight the few and hope the many remain invisible.

The irony is almost poetic. The same political machinery that once accused Saraki-era governance of being elitist now presides over a system where elite silence meets mass suffering. The same chorus that weaponised the phrase Otoge, meaning “enough is enough”, has now delivered “more than enough” of hardship, hunger, and hollow promises.

And while we’re here, let’s not ignore the arithmetic of poverty. The refusal to implement a meaningful minimum wage cum the exclusion of Retirees from the so called Mininmum wage benefit is not just an economic issue; it is a nutritional policy. When carers cannot afford food, children suffer first. It’s simple, tragic math. A government that refuses to lift workers and Senior Citizens out of starvation wages should not be surprised when children end up starving.

We must also stop mistaking minimalism for prudence. A governor who refuses to invest in people’s welfare is not being prudent; he is being negligent. You cannot save your way out of hunger. You cannot govern with press releases while your citizens queue for emergency nutrition packs.

The truth is painful, but necessary: Kwara is no longer fit for a child. And the rot didn’t begin in Abuja; it began in Government House, Ilorin. A state once hailed by UNICEF for policy foresight is now on a list no state wants to appear on. That decline is not abstract. It has names, faces, and empty stomachs.To the discerning Kwaran, this moment should be sobering. Good governance is not about Instagram posts or ribbon-cutting ceremonies. It is not about spinning stories of prosperity while ignoring the evidence of poverty. The presence of 300,000 malnourished children is not a data point; it is a verdict. It says this administration has failed.

And so, we return to the lesson Saraki’s administration taught, whether critics admit it or not: governance is not about slogans. It is about systems. It is about people. It is about children, because they are not just the future, they are the mirror that reflects whether a society is just or unjust.

Today, that mirror is cracked. And no amount of spin can polish a broken reflection.